It’s been a long time since I could sit with a video game for more than 20 hours. Yet, heroically, I deferred my app-withered attention span to play one of the slowest games around. My recent playthrough of Fire Emblem Engage took 60 hours. And I spent that time doing actual math — stat growth rates, hit percentages — when I could’ve watched The White Lotus, then Succession, then finished The White Lotus again.

I thought the game was great! Even though the writing is… really really bad. Here’s a scene between two characters: the posh, cartoonishly wealthy noble Citrinne and the rustic, capable warrior Lapis.

LAPIS: I wish my family tree was as impressive as yours, but… things are different for me.

CITRINNE: Oh, Lapis. You and I make a perfect match.

LAPIS (visibly surprised): Huh?

CITRINNE: You see your family’s social standing as a hindrance, while I see lack of strength as mine. Each of us has what the other lacks.

LAPIS: Huh. You’re right.

Remove every line of dialogue from the above scene starting from the end. At no point will the scene lose its meaning. Fire Emblem is subtextless, subtle as a buzzsaw, elegant as a router setup manual.

Other, higher-degree issues plague the game’s script. One princess character wanders through poor parts of town wearing expensive jewels, then preemptively strikes commonfolk that eye her riches. (This is just an aside in a getting-to-know-you scene, not a horrifying character study. She’s ostensibly one of the good guys.)

Games can tell great stories. But fans adhere just as strongly to games with bad stories. “Why does this person ride a wolf? What does that say about husbandry practices in Elyos?” The shibboleth among Fire Emblem fans isn’t “Well, you see-,” it’s “WOLF KNIGHT AWOOOO.” Mystifying droves of fans (like me) gather around flawed games in a real, ardent way, not a “guilty pleasure” type way.1

The bar for writing in video games just seems lower than in other mediums. Popular ideas about why that is leave audiences holding the bag — Doom creator John Carmack infamously took the stance that “story in a game is like story in a porn movie: it’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.” Buying this argument perpetuates the idea of games as lowbrow time-wasters and players as lab mice with dopamine buttons. Publishers and critics, not fans, feed this beast.

Just to go ahead and address some of the common explanations you’ll find for bad game writing:

Fire Emblem Engage includes over 2,000 scenes like the one between Lapis and Citrinne, each fully voiced, each unrelated to the game’s main plot. Video game development tasks increase combinatorially due to the branching-path nature of the medium. For example, if you add one more character to Engage, you’re immediately on the hook for something like 70 more scenes. Ergo, game writing is hard. But it’s not your job as a critic or audience member to pity a work by ignoring its glaring faults. I mean, don’t go around saying video game writers have it easy. Don’t go around defending a bad script, either.

Video game writing is bad because it relies on misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, racism, or military propaganda, and because it’s dominated by male whiteness on the industry side. (It bodes poorly that the number of women in gaming fits on a Wikipedia list.) The thing about this argument is, it’s all true. Laura Kate Dale, Jim Sterling, Anita Sarkeesian, and Jamal A. Michel are great voices on this subject. Supposing we could about-face every deficiency in gaming culture, though, I still think writing in games would fall behind movies, TV, novels. Like, Engage relies on some heavy “might makes right” classism, but even simple dialogue exchanges often fail on the level of principle.

Players want flashing lights and buttons to push, not meaningful experiences. No one involved really cares about their craft, and publishers will fire talented writers for no good reason. The John Carmack philosophy. This is bogus. Execs know that a well-written game performs better than a badly written game. Breakouts like 2018’s God of War and The Last of Us count among the greatest stories ever told in games and came with googly-eye levels of financial rake-in. That success originates from fans’ appreciation of strong narrative.

Let’s keep talking about these two big successes, because it’s where we’ll find one of the medium’s biggest troubles. God of War and The Last of Us belong to the same genre: third-person action adventure.

Over half of all Game Awards “Game of the Year” nominees follow the action-adventure or action-RPG formula. Every winner, except Overwatch in 2016, falls into one of those two categories. And I love plenty of these games! Each represents some kind of unique approach. But of all the things a game can be, that the upper crust is so replete with games about staring at a buff dude’s shoulder for 30 hours… maybe we have a variety problem.

Narrative beats in action-adventure titles are delivered as a reward for gameplay. You succeed at a puzzle or combat encounter and you receive a plot coupon, which you can exchange with the game developer for a cutscene that moves the story forward. Games like these earn one of the highest praises available in AAA gaming: they are cinematic, referring to the writing and composition of cutscenes.

Almost by definition, this structure means that cinematics — another word for cutscenes — are completely disconnected from the experience of gameplay. It turns out that The Last of Us made for an incredible TV show, but is it any surprise? You could already find plenty of “game movies,” silent playthroughs of Joel’s quest that either speed through gameplay segments or excise them entirely. All the plot, none of the pesky fun.

The burden of cinematics doesn’t just fall on Game of the Year-type games. It falls on Fire Emblem Engage, which marks the development of your army with disjointed vignettes about tea parties, laundry, yam drama — and it’s like, dude, the world is pretty much ending, your best friend just died, why are we still talking about pamphlets.

Clint Hocking identified the gameplay-to-cinematic disconnect in 2007’s BioShock, a first-person shooter, in a debate so prolific it got a bunch of regular people to learn the phrase “ludonarrative dissonance.” Your main character mows down hordes of living people — it’s a shooter after all — and then in a cutscene extolls the virtues of pacifism. That’s ludonarrative dissonance.

Modern games adapted by making themselves about examinations of violence. Dissonance solved, right?

Sadboy up your protagonists, include a Good Ending and a Bad Ending (choice!), scatter in a few optional dungeons. You still won’t have solved gaming’s deepest disconnect: that games are games, not movies. Outlets like the Game Awards send a message that the best thing a game can be is a movie, and that cinematics are both the best way to tell a story and the only path to acclaim.

Can we develop a language for appreciating games that doesn’t rely on other primarily plot-driven mediums?

One technique fans have latched onto is called “environmental storytelling.” FromSoftware, the makers of Dark Souls and Elden Ring, are the archetypal masters. You will rarely find a meaningful cutscene in a FromSoft title. Characters will say things like “the legend of Artorias art none but a fabrication,” and this is the first you’ve heard of Artorias and also the very first thing this character says to you and also the character saying it is a cat. To learn more, you need to find a ring in a forest graveyard, speak to a masked priest in a flooded town, and fight Artorias in the past using some time travel shenanigans. An entire genre of YouTube has devoted itself to untangling these narratives.

But FromSoft games are some of the least accessible examples of this technique. Horizon Zero Dawn, another Game Award nominee, answers most of its deepest mysteries via stumbled-upon emails, not dialogue.

Environmental storytelling works because it plays into the unique affordances of games, the things a game can do that no other medium allows for. “Stumbling upon” is patently uncinematic, but it’s core to the experience of video games.

You know what else exploits the affordances of games, rather than cinematics? Fire Emblem Engage!

I’ve glossed over the details of Engage till now, but let me get into for those unfamiliar. You may have guessed from “princess” and “wolf knight awoo” that it’s a fantasy game. You play a valiant hero in command of a small army tasked with saving the world. Fire Emblem is the ur-tactics game — think oldschool D&D or like, anime checkers — and it’s one of Nintendo’s flagship franchises, just five years younger than Super Mario. Besides the strategic gameplay, the franchise’s rotating casts of characters are its main draw.

Cinematic writing uses goals, fears, or empathetic character writing to get you invested in characters. Engage uses permadeath, meaning if you mess up in battle you can lose someone forever. The character actually dies.

I became very attached to some of the characters in my Engage playthrough. Even Lapis, the yokel swordfighter from earlier! And it wasn’t because of strong character work. I loved Lapis because she could attack twice and had like a 30% crit rate. I was invested in her character because of the literal time and resource investments I made over the course of my playthrough. Over time, that practical attachment turned into emotional attachment. I spent real hours replaying sections until my favorites survive.

All games are, in a sense, roleplaying games. Fire Emblem puts you in the mind of a battlefield commander. Your goals become like a commander's goals -- win the battle, minimize losses -- even though you personally are not militarily inclined. Designers convey experiences through practical problem-solving and agency, not text and subtext. Games are not primarily a narrative medium.2

Consider how both “strong writing” games (The Last of Us) and “weak writing” games (Engage) wind up in the spotlight. Both can be fun. But the reverse is not true: a boring game can’t carry a great story. I say this having bounced hard off of many Game of the Year titles mentioned above, not because of bad writing but because ohmygod i can’t throw my axe at another jar if i find one more crafting material i’m going to break my thumbs.

To say Engage is Good Art… maybe that’s a little far. It’s open to plenty (plenty) of critique. And as a Nintendo mainstay, it’s working under unique pressure to conform to an existing formula. What I mean is, I don’t say any of this to try and “fix” Engage. We got exactly the game we were meant to get.

That said, I do think other tactics games — ones with a story to tell rather than a legacy to uphold — should seek out uncinematic success in the genre. XCOM 2 is a good example of a tactics game that uses practical agency to support its narrative. In the first game you’re the long military arm of a unified Earth government, but in the sequel humanity has lost its war. Now you’re the resistance in a world ruled by aliens. Stealth mechanics were added to reflect your new underdog status.

But tactics games can be sort of oorah. Games are about becoming, and we can become so much more than military commanders.

Imagine a murder mystery in which the detective never knows if they got it right or wrong. Movies can’t explore choice and guilt that way, but it’s at the heart of the historical mystery game Pentiment.

Imagine you work a desk job for a growing autocracy. Now, someone asks you to look the other way. You might get reprimanded, but a key piece of the revolution will fall into place. Would you do it? What if your livelihood depends on that job? What if there’s no guarantee the revolution is noble? Games like Papers, Please and Not For Broadcast demonstrate how failure can be used as a game mechanic.

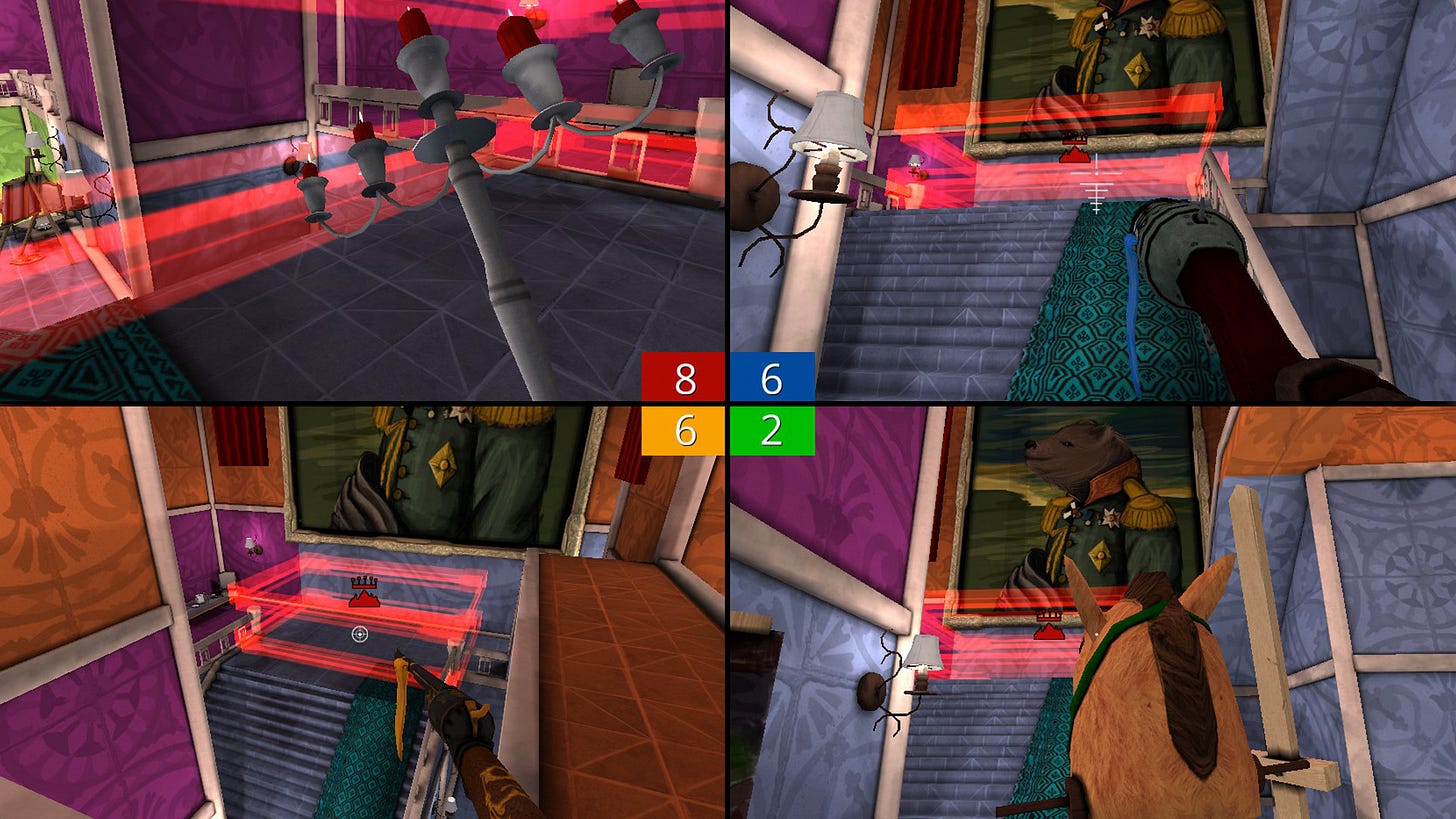

Even non-narrative games create novel shared experiences. Before multiplayer games migrated online, everyone shared the same screen divided into squares. Screencheat is a multiplayer shooter modeled on that memory. It uses technical limitations from the history of games as its core feature, and in that way it’s a game about nostalgia.

Neglecting the use of agency in games is like neglecting the use of paint in painting. It’s some overblown version of that exhausting “the book was better than the movie” thing, a fixation on your memory of an artwork with no consideration for the tools used to construct it — tools that vary widely from screen to page to PC. Games can operate under a narrow definition of narrative as plot and dialogue. But the use of agency to deliver direct experiences produces some of the most powerful experiences in media.

Fire Emblem is flawed, for sure. But it succeeds in ways inaccessible to other mediums. Learn its lessons, and we start to develop a language around the artistic tools unique to gaming. Write off its achievements as the shared delusion of tasteless fans, and we all stay in the feedback loop of games-as-cinema.

And slip further into the delusion that every franchise needs a movie.

Thank you for reading!

For what it’s worth, I’m actually thrilled that The Last of Us is having a moment with non-game audiences. Artists in gaming need more legitimacy.

Last post I said I’d write about TikTok, and that piece is in the pipeline! But boy is research taking way longer than I thought. Currently 14 hours in. Look forward to it, and drag this email to your Primary tab so it doesn’t get lost in Promotions. See you then!

DR

@ Fire Emblem fans, I use “Fire Emblem” and “Engage” sort of interchangeably in this essay. Rest assured I know the quality of writing changes game to game — I got into the series with Three Houses. But like, Engage is a pretty low bar ngl.

This argument comes from C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency As Art. Nguyen is sort of the high priest of whatever it is I’m doing here, and I’ll examine his work much more in future.

Game design philosophy might explain some trends mentioned in this article. Some developers start with game mechanics and build the story around that or they might start with story and figure out game mechanics as they go. Like hollywood blockbuster movies, the similarities between big blockbuster games may be due to high costs and the need to achieve commercial appeal so we get less experimental games and more third person adventures.