I likely don’t have to tell you why being good at video games isn’t a moral victory. You are a reasonable person with sensible values (and, can I say, great hair). Less well-composed are the many Elden Ring players who came from the woodwork this past month to berate journalists, streamers, and casual fans for calling a spade a spade: the game’s newest expansion, Shadow of the Erdtree, is bone-shatteringly difficult.

Too difficult? I don’t know! All I know is that when gaming discourse breaches containment — to the extent that Forbes is publishing your game’s patch notes — something has gone seriously awry.

Games in the genre of Elden Ring have the reputation of being either tough-but-fair (generously) or player-hostile (less generously). They’ve cultivated a committed fanbase of people who exult in punishment, who believe their spirits have been purified by suffering, and who lord that pride over others who fail to beat the game.

And this is the exact language that I take issue with: beating a game — defeating, conquering, subjugating, subduing. I love FromSoft games, including Shadow of the Erdtree, and I can attest that winning one can feel like summiting a great, unfeeling mountain. Only, it’s not a mountain: it’s an obstacle course. The difficulty was constructed before I got there, along with every other part of the experience, by the designer. It’s the opposite of unfeeling.

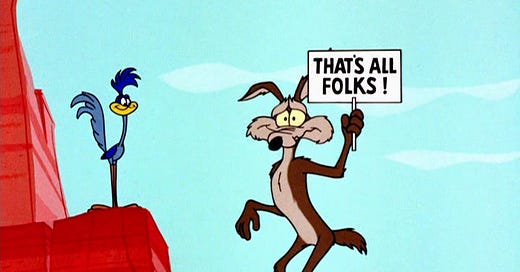

Let’s talk about Wile E. Coyote.

In the old Road Runner cartoons (I’m told), Wil E. Coyote would sometimes chase his quarry off a cliff. When he did, he didn’t fall right away. He looked around, up, down, saw the chasm beneath him, held up a sign that said “oops” or something similarly understated, and only then plummeted.

“Coyote time” is the term coined by game developers to describe a kind of hangtime. Very specifically, it refers to a few milliseconds after your character has left a platform, during which you can still jump. The effect, though imperceptible, is that of kicking off of empty air. It’s one of many forgiveness mechanics in the platformer Celeste — still a difficult game by anybody’s definition.

Forgiveness mechanics are usually billed as simply smoothing out a game’s rough edges, but I think that’s understating it. If I run off the edge of a platform in Celeste, that’s a mistake on my part. Forgiveness mechanics don’t improve game feel in the way that, say, better graphics improve game feel: they correct the player’s mistakes. They make games easier in subtle ways to make them fun in more obvious ways.

Despite Elden Ring’s reputation as an “unforgiving” game — a game where the air is the air, and what can be done? — it’s also chockablock with forgiveness mechanics like invincibility frames, super armor, and tiebreakers that favor the player. The game paves the way for success in innumerable small ways.1

But why think small? In the first-person shooter Receiver, the player is tasked with managing every step of reloading their weapon, from ejecting the magazine to toggling the safety. In traditional FPS games, all it takes is a measly press of the R button. Isn’t this a kind of forgiveness mechanic? Aren’t hit points?

Why are we pathologically incapable of admitting when we’ve been forgiven?

It might come down to the perceived conflict between difficulty and accessibility2. The two are inversely proportional: the more difficult a game is, or the less accessible it is, the more we feel like we’ve outwitted the game when we succeed. And when we think of games primarily as tests of skill, a game that’s maximally difficult is more game than one that’s maximally accessible.

This is a false dilemma. Not only have many of the most influential games of the last decade proven that difficulty is unnecessary for a satisfying game — Minecraft, Gone Home, Stardew Valley, Doki Doki Literature Club — the inverse has never been true. No game has ever been completely inaccessible. A game isn’t a game without somebody to play it.

Accessibility is the main project of game design. If the designer wanted to “beat” the player, they could do it 100% of the time. Instead, the artist seeks to create an experience accessible to the player, and while challenge is one kind of experience they can create, it’s one of infinitely many: community, narrative, spectacle, reflection, wonder, peace, care.3

It’s why, though I agree that Shadow of the Erdtree overtuned its difficulty, I don’t necessarily think it should be changed. FromSoft was always up front with its design philosophy, with director Hidetaka Miyazaki calling it an experiment in what can be “withstood by the player." It’s not for everyone, but not every game provides every experience. Marvel movies were designed that way, and we all saw how that went.

And it’s why I get so frustrated with players who feel superior because they succeeded in a system rigged for their success. All games are collaborative. All games are social. To then reject the hand that held yours, and claim that you achieved mastery under your own power, is more than just a disservice to the designer. It’s a kind of self-exile.

None of this maps cleanly onto the real world. Games work because they present simple goals with clear ways to reach them, and forgiveness mechanics work by smoothing out the path between those ends and means. Reality lacks this simplicity. C. Thi Nguyen writes, “Our abilities sometimes fit our goals in the world, but so often they do not… We do not fit this world comfortably.”

This world doesn’t have coyote time, either. In fact, the only forgiveness in the universe is what we offer to one another. We just need to stop gloating long enough to realize it.

Thanks for reading!

FromSoftware is the developer behind Elden Ring and the Dark Souls series — I’ve talked about them before, maybe too much! I promise I won’t mention them again until, I don’t know, post #100.

DR

An exception that proves the rule can be found in the fact that veteran players, who habitually move the goalpost on what constitutes a “valid” way to play the game, never dismiss complaints about the game’s finicky camera controls. Getting good, apparently, doesn’t include learning how to manage this auxiliary element of gameplay.

I use “accessibility” broadly here, i.e. the ability for people to play your game. This includes game design that supports players with specific disabilities, certainly, but ability is a spectrum. Accessibility modes are catered to certain groups of people, but a generic decrease in difficulty grants access to everyone. (See note on Another Crab’s Treasure below.)

Luke Plunkett wrote brilliantly about this concerning the soulslike game Another Crab’s Treasure, which includes an accessibility feature that gives your lil crab a gigantic firearm. “This gun doesn’t make the game easy,” he writes. “It simply removes all difficulty whatsoever.” It transmutes the game from a difficult game into a vibe game.

Celeste is great in terms of forgiveness mechanics. Quick GMTK plug (my favorite game design youtuber): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yorTG9at90g

I think it's nice that it's coyote time, not coyote distance. It's not a larger ledge, it's a few milliseconds to spend however you want. A nice little coyote grace period, not unlike i-frames after you get hit by something in other games