#10: A people's history of caffeine

How Sufis sipping coffee turned into Substack writers silently pounding Charged Lemonade

Caffeine is near and dear to my heart, which is to say it’s usually in my bloodstream.

It’s weird that I feel like I have to state my credentials here, but daily caffeine usage is so ubiquitous (85%!) that just saying I have a cup of coffee every morning makes me no more of an expert than, for example, every early-morning commuter in the country.

So, credentials time: When I was 14, I got it into my head that if I wanted to ask someone out on a date, I would rather say “want to go get a coffee” than “would you like to get a coffee while I drink hot chocolate or something.” So I started on coffee.

My relationship with sleep is rivalrous on a good day. I drink coffee early to fight tiredness, and I drink coffee late to stay awake. At my height I would hit around seven cups a day, although I drank a lot of soda at that time, too — 1,118 Diet Cokes in 2017, which I learned by saving bottle caps. I cut back. I drink four cups now, but one or two of those are usually decaf. I’ve got a cold brew in arm’s reach while I write this.

I never crossed over into energy drinks. They felt like too much, because they were branded as Too Much™. But a funny thing started happening, where I would grab a Starbucks Double Shot or a Refresher, and come to find out that they were disguised energy drinks all along. Nothing is safe from caffeine creep.

Panera got caught slipping caffeine into their Charged Lemonades, resulting in the death of 21-year-old Sarah Katz. The narrative you’re likely to have heard is that Katz, a caffeine-sensitive college student, drank a Charged Lemonade without knowing about its caffeine content. Panera hardly advertised it. As a result, the company added a warning.

This version badly buries the lead, which I didn’t fully understand until reading Ernie Smith’s writeup. Panera didn’t sneak a teensy bit of caffeine into their lemonade and then forget to say anything. It loaded 260 milligrams of caffeine into 20 ounces — comparable to a 20-oz dark roast, except that a dark roast is hot and bitter, and 20 ounces is the largest size on offer. Charged Lemonades are cool and sweet, and come in 30-oz cups and bottomless carafes. I get a little jittery after about 24 ounces of strong coffee. You could easily throw back twice that in lemonade before you realized anything was wrong.

I’m surprised more hearts haven’t exploded as a result.

Panera deserves all the blame for its negligence. But I also want to step back and look at the larger picture around caffeine — its history, the history of marketing around it — because I think we’re unwilling to say what needs to be said about its use. We need to be a lot more honest about why we like caffeine.

A great distillation of what I think is the prevailing attitude towards caffeine comes from “Happiness is a Warm Coffee,” an article that ran in The Atlantic’s happiness column. It’s basically a liturgy in praise of caffeine, outlining what it does in the body (blocks adenosine, the neurotransmitter responsible for tiredness) and some of its health benefits, like preventing heart disease and Parkinson’s and reducing all-cause mortality.

It also discusses caffeine tolerance and addiction in some pretty interesting ways, like this section about increased caffeine use over time:

This leads to a state of tolerance, in which caffeine has a smaller effect after chronic use. However, this “problem” is really just an opportunity to enjoy more coffee.

And this cute anecdote about the author yelling at his wife:

Recently, noticing the increases in my consumption over the years, she innocently proposed that I “take a little break” from coffee. The very suggestion made me fly into a rage. “Here’s an idea,” I replied, heart rate soaring. “Why don’t we just live apart for a year so it feels more like it did when we were first married?” An overreaction? I think not.

What does this tell us about our attitude towards caffeine? It’s a complete blind spot. We know it’s an addictive substance, yet we cling to fringe medicinal benefits by way of justifying increased caffeine use over time.

We’re kidding ourselves if we imagine heart disease is why people take caffeine. The history of caffeine (or the history of coffee, which in the West is the same thing) predates modern medicine by several centuries, covering a few big cultural shifts.

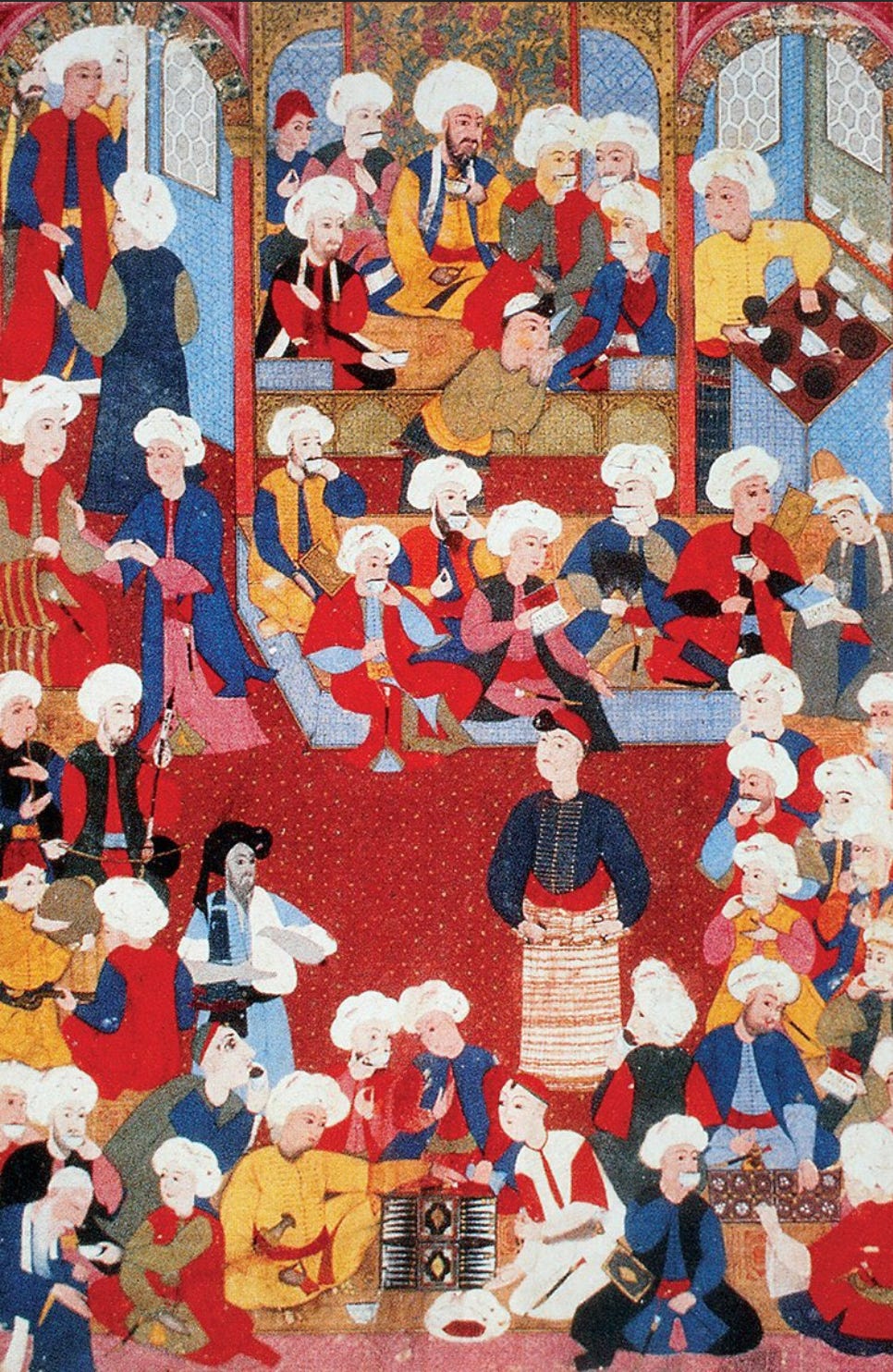

Coffee originated in the Islamic world. Sufis used it to stay awake during midnight prayers. Coffeehouses eventually opened in cities like Istanbul and Mecca, and were known as pleasure hubs for conversation and the arts. Poets performed, religious leaders gave impassioned sermons, satirists poked fun at power. Rulers would occasionally attempt to ban coffeehouses. Those bans never stuck.

When coffee came to Europe, Protestant countries took a liking to caffeine as a stimulant and antierotic. One theory goes that coffee, having replaced beer and wine as the drink of choice for many Europeans, transformed a constantly tipsy population into one capable of supporting the Enlightenment.

Physicians gave it a mystical, Orientalist cast. The first coffee ads to appear in London claimed coffee “quickeneth the Spirits,” “maketh the heart lightsome,” and cures everything from headaches to gout.

English coffeehouses did appear as places of academic discussion where class was leveled, like in Istanbul. But they disappeared in part because of the Protestant obsession with preventing idleness: coffeehouses became overrun by important political and religious conversation, not leisure. People stopped going to coffeehouses when they stopped having fun.

The nail hit the coffin late into the Industrial Revolution, when researchers discovered that a midday caffeine boost increased the efficiency of factory workers. Thus, the coffee break: all of the stimulating benefits of caffeine, without any of the leisure. Coffee in the US was marketed as a necessity for salt-of-the-earth laborers, and it’s been that way ever since.

Cafes are everywhere now. But they’re full of people (like me, right now) typing dutifully on their laptops, or conversing in moderate tones. They follow the Protestant model, serving medicine that helps you work. You drink caffeine when you need a boost in the morning. You drink it when you hit a slump at work. You drink it to be a beast. In short, you drink caffeine when you need to be awake, especially when you need to be awake against your will.

An Ottoman poet described coffeehouses of the sixteenth century as “the hospital of the hedonist.” Now, they’re hospitals for the overwrought. Caffeine is the cure for tiredness. How can a cure be dangerous?

Compare that to how we think about bars, which are similar to Ottoman coffeehouses in reputation. We don’t think of alcohol as medicine, though in very small amounts it confers some of the same health benefits as coffee. We think of alcohol as poison. But there’s no strict medical definition of poison, it’s just any substance that hurts us. More specifically, alcohol is a drug: a little bit of poison that we tolerate because it feels good.

There’s a Charged Lemonade ad, “Behind the Counter,” that describes the making of the drink in a way that’s darkly hilarious in the context of its body count. A talking head says they’re taking the flavor of their lemonade “to the next level.” Did they invent a never-before-tasted flavor? Did their researchers discover a new way to fire taste receptors?

They didn’t. In fact, caffeine on its own is bitter. Panera increased the quality of its lemonade along a completely different axis: it added a psychoactive component. It drugged its lemonade.

This is how we ought to think of caffeine, and it’s how we never allow ourselves to think about caffeine. When we deny its history as a social drink, it’s because we’re denying a rebellious fact: that it’s fun to do drugs with your friends.

When you subscribe to the belief that tiredness is a disease, and caffeine is the cure, you think of a caffeine overdose as too much of a good thing. When you view caffeine as a drug — a little bit of poison that makes you feel good — it becomes clear that an excess of caffeine comes from a fault of moderation. (In the case of Charged Lemonade, the fault is Panera’s.)

Remember that coffeehouse bans never stuck, although due to the threat they posed to power such bans were attempted. How did power circumvent our resistance? It made the drug into a medicine, then prescribed caffeine back to us on its own terms.

The solution? Get a group of friends together and go on a Panera crawl. Drown out the smooth jazz with rough conversation. Feel the buzz of a Mango Yuzu Charged Lemonade while you dissect Marx and Engels. Reclaim the social benefits of caffeine. Reject the medicinal ones.

Thanks for reading!

My favorite fact that didn’t fit into this post is that Catholic priests distrusted coffee when it came to Europe from the Islamic world. They called in the pope to get it banned. Unfortunately, Pope Clement VIII ended up really enjoying coffee, and claimed to “fool Satan” by baptizing it. So enjoy your good Christian coffee.

DR

Good! I’ve never had coffee before! Now I’ll check out this hip new drug knowing the Pope has baptized it. Do you think he could baptize heroine for me too? 🥹

This should really be submitted to the NY Times Opinion section. it would fit right in.