Review: A History of Goldsberry

A place that used to be the sea. A town destroyed by fire. A baron and his buried treasure. This is the story of Goldsberry, a village on the road to oblivion.

This is not a story about fun.

What follows is my submission to

’s 2024 blog contest. It’s a piece I’ve written off and on for the last five years, and it’s very close to my heart.This is a story about memory.

Abandoned houses aren’t empty. You won’t find any vacant rooms, wood peeling, one chipped window clicking in its frame. They are full. Sunbleached photos and flags still hang on the wall. The floor is invisible beneath a sea of outmoded brand labels, hats, prescription bottles, dozens of pairs of blue jeans. Heat pools in reservoirs. All things eventually find their way to settle here.

Cities keep meticulous records of their uninhabited spaces, and sooner or later someone will come along and make them truly empty. No one, on the other hand, checks up on the old trading posts of northeast Missouri, and anyway it was a northeast Missouri trading post I stepped into that summer.

I heard the legend of Goldsberry from my old acting teacher: a wealthy store owner abducted by teenagers, tortured for the whereabouts of his buried treasure, and ultimately set aflame.

The ghosthood and the blaze of that story, in my mind, fixed it firmly in the past. No specific point, just beyond the mists of time. But beneath the blue jeans, among the wreckage, the unpaid bills and TV guides were all dated 2002.

Newspapers from the time begin to tell a fuller story — a story about roads, and a place that used to be sea, and above all, fire.

…

In the vast ocean of land beneath America’s vanished seaway, tallgrass waves crash on asphalt shores, and rumors spread like wildflowers.

They told that Frank Shimek was no mere store owner. His own eulogy would eventually call him the “mean miser of Macon County,” and those that knew him would say “finally” when they spoke of his demise. He fished pennies from the donation trays of gas stations. He sprayed mustard on the wood-paneled wall of a diner. He beat his kids. He hid a fortune.

Six young pirates came from counties around on a caravel of factory parts — a Ford, or a Chevy — hearing how Shimek moved quietly, then “[pulled] out a wad of cash that would choke a horse.” He sold counterfeit arrowheads out of Goldsberry’s ancient general store after the highway came through, spent the rest of the day sitting on his porch in dirty underwear, spent nothing, and in no way seemed to deserve what he had.

I don’t know if he deserved what he got. But the fact is that an ice storm knocked out the town’s power and sealed it away. Exactly what happened inside when the pirates came will remain a mystery, but eventually a shot rang out, and a fire started.

Tomorrow it would be discovered that the fire’s heat boiled the paint off of cars a street over. Only one of the two iron safes was missing, which would soon be found in a chicken coop not far away. The other was the fire’s share. Six perpetrators, ages 17 to 20, would eventually be apprehended. First-degree murder. Second-degree arson.

But tonight, the lone light of a fire brings Goldsberry into quiet constellation with the great Midwestern sky, its tinder the wicked soul within.

…

We parked on the shoulder of the road, because what else was there? All of Goldsberry was a criss-crossed street, each building sagging or fallen through. Even around the general store there was nothing that bordered a definite interior space. The barn with the precarious loft still warned, “NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ACCIDENTS. FIRE. THEFT.” Tree limbs made half of the homes impassable. And none of us tread past the house with the lights on.

Still, the presence of mail intrigued me: the only post office in Goldsberry had closed in 1974. A quick census search revealed that mail was delivered from nearby Ethel.

We traveled the short, broken road to a town on an embankment. The high-peaked roof of a church on the hill implied one of those New England harbor towns, but instead of gray ocean, interminable train tracks sprawled below. Over 100 trains pass through Ethel each day, I’m told, which is more than people who live there.

The history of this town goes a long way towards explaining the condition of the region. Both Ethel and the nearby town of Elmer were founded by the same railroad company. Local legend has it that an employee named one town for his daughter, and the other for his son.

Such is the level of pioneersmanship that erected so many crossroad towns in this neck of Missouri: towns so cheaply minted that they could be handed out like Christmas gifts.

I caught the county fire chief digging ditches in front of the bed-and-breakfast, called the “Recess Inn” for its former life as a school outbuilding. We said what little there was to say about Goldsberry, then spoke of Ethel, and New Cambria where he ran a cafe on the side, and Marceline where (he said with pride) Walt Disney was born.

He spoke cheaply of towns, because a “town” is not the unit of civilization in most of America. Rural life consists of counties, the settlements themselves more or less interchangeable. Schoolkids in Ethel were bussed in from Goldsberry and Callao (CA-lay-oh); the glittering city on the hill is the county seat of Macon; the nearby college town of Kirksville is a weekend getaway; the Times Squares and Tokyos that bother most city-dwellers exist only in the abstract. They simply aren’t worth the attention.

I wondered if this all takes the sting away, a little, when it all goes up in flames.

James Medley Hill wrote The History of Goldsberry in 1991. It began, “The centennial year for the village of Goldsberry came and went in 1982 without any observance.”

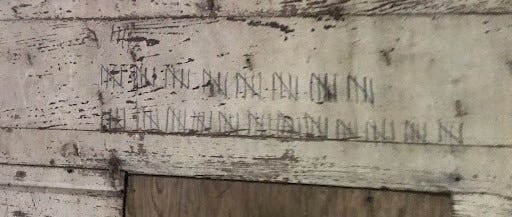

The pages that follow contain a map of the town, and each building is numbered, and each number is listed alongside every tenant the building ever had. (I recognize only a few of them. Frank Shimek’s name is crowded at the very bottom of No. 10, Two Story Brick Building — First Floor.)

Hill’s map, hand-drawn, is difficult to parse. I struggle to connect its lines and boxes onto the real scattering of buildings. Even the aerial view on Google Maps, which I now compare side by side with his drawing, only vexes me: the block of buildings numbered 10 through 14 are strangled by unkempt tree cover. The rest is beyond recognition, or completely gone.

I recovered only a few pages of this history from the Macon Historical Society. I don’t have the asides Hill added between each exhaustive list of names, the store owner who bought too much green ice cream and began giving scoops away to any child who walked in; the whole town gathering around the barnside where movies, at the time a newfangled technology, were projected; baseball tournaments in the fields between towns.

Regarding Goldsberry, Hill continues, “It is the purpose of this narrative to preserve some of its history before it all fades into oblivion.” Tucked between lists of names, in the shelves of the archive in Macon, hours from Kirksville, a train ride away from the world — details like these come closer than anything to showing me what life there was really like.

At the same time, the vignettes smudge together with other accounts I remember from my research. (Did Hill play baseball? Was that someone else?) Either Hill failed to preserve Goldsberry, or else it’s the way of all memory to compress: lives into names, names into lists, moments into scenes into stories with no beginnings or endings. And when the places that contain those stories burn, what then? Are the moments themselves caught up in the inferno?

I read those names again and again, the light dying.

A few spaces above Shimek, the name John Hawkins appears. At 93 years old, he is the last son of Goldsberry.

Where settlements dot the plains like islands, roving doctors travel between the homes of folks otherwise forgotten, and it was one of these doctors that introduced me to John. The doctor set up an interview for us at his dispensary. These were the dog days of lockdown, and everything was antiseptic. Still, I took every precaution I could think of, acutely aware that my negligence risked a kind of extinction.

John Hawkins bent into the room. Physically, he gave the impression that he wasn’t totally there. My words passed through him. This was my own fault: I was not yet a journalist — Goldsberry had not yet made me one — and in the days before the meeting I was frantically googling tips for this, my first interview.

I didn’t know how to talk slowly. I didn’t know how to focus. I simply sat across from John Hawkins, and I asked him to tell me everything.

And he did. He told me about the house he grew up in, about rumbling with the boys from Gifford, about the movies on the barnside (he called them “talkies”). He told me how he asked his wife to dance. He told me how the only time he ever left Goldsberry was to fight in Korea, and how the world gave him no reason to press further. He told me about Shimek.

Hours passed before I posed the questions I’d needed to ask all along: How does it feel to know that the place where you were born will die with you? What happens when the lights go out? Why can someone like Shimek become so synonymous with a place that when he burns, a whole world burns with him?

These were not good questions.

He told me, blankly, how everyone had already fled. They punched their tickets in Kansas City or Chicago. Long before Shimek was pruned, the town had ceased to grow.

I searched him for the peace that comes with fading away — how a man from a vanishing town, himself mostly vanished, can refuse to race the sun and instead live unbothered in the dusk. He said only, “Times change.”

Fire is the mother of ghosts, and all stories about fire are ghost stories. Time destroys. Fire creates. In the ghost stories that have passed on to me, from John Hawkins and James Medley Hill and Frank Shimek, memories of Goldsberry flicker and disappear like tongues of flame.

Even this very document is an illusion created by the notes, recordings, and recollections I made of my time in Goldsberry — a memory of a memory. Who knows what my mind has bent to serve the arc of a narrative?

Will I admit that James Medley Hill never wrote The History of Goldsberry, but instead wrote The History of Goldsberry and Tulvania, its sister town, burnt and disassembled brick by brick long before Goldsberry summoned me?

Will I admit that I not only feared the house with the lights on, but the tenant inside, whose hermitage is tragically common in the far-flung parts of Missouri? Will I admit that he has as much say in the memory of Goldsberry as anyone? That the last fire in the village will be his?

Every light will eventually illuminate what Goldsberry leaves behind. From the last shotgun home beneath the trees, to the late summer of 1931 when “A Day in Goldsberry,” the earliest account of the town I could find, was written.

The writer describes “a lovely green emerald dropped down on the landscape.” A great peach tree breaking beneath the weight of its bounty. The talk of the town, a new school and its winsome superintendent. Every screened porch open for long conversations. Lilies, and pools of fish, and great stone rabbits, and beautiful, well-kept roads.

None of what that traveler described remains. The forgotten sea still rises, all-obscuring. What remains is the profusion of lights in the wider sky, its constellations named not for their brightest stars, but for the stories they tell.

Thanks for reading,

DR