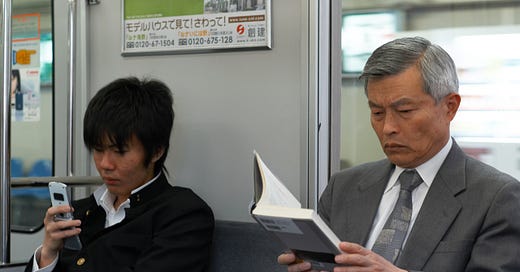

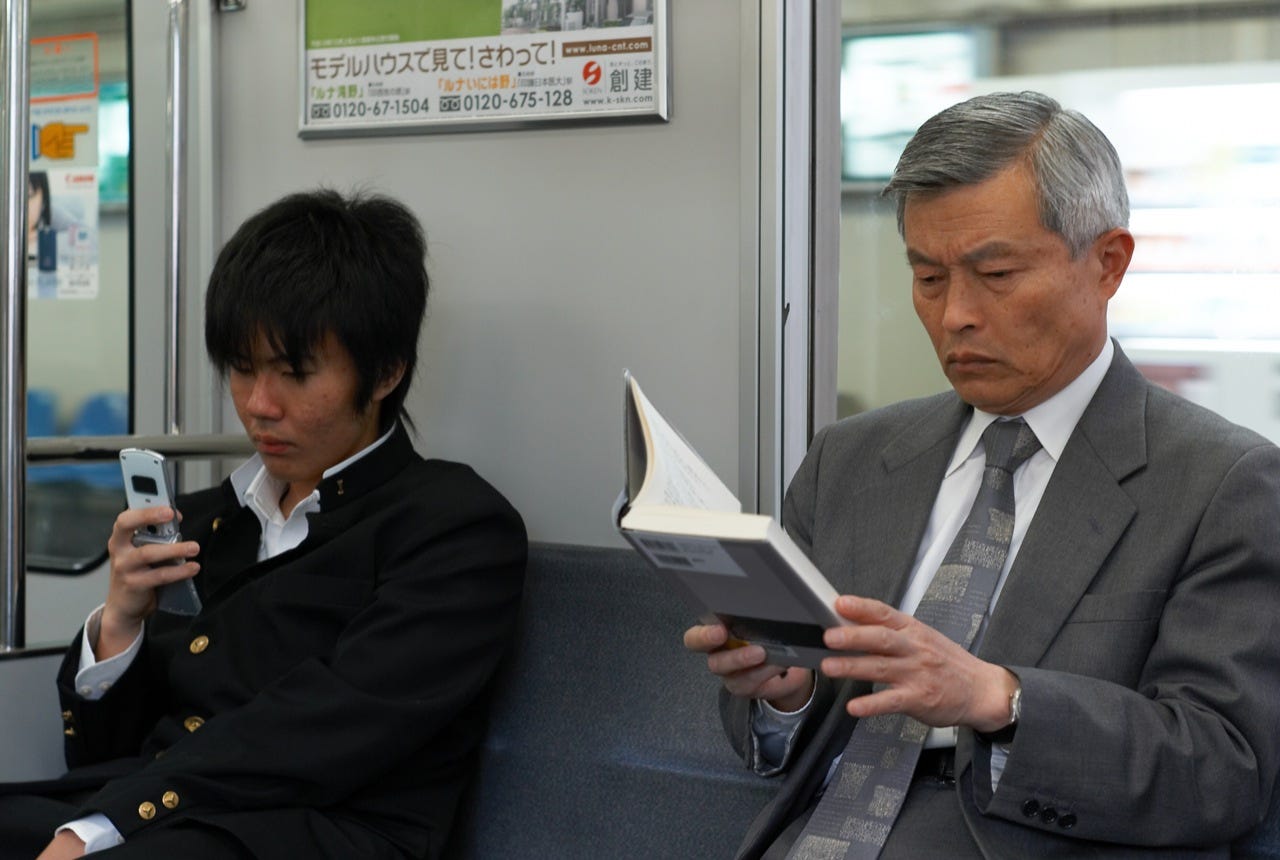

Four of Japan’s top five literary best sellers in 2007 were written on cell phones.

The authors of cell phone novels — associated mostly with women aged 10-29, the Twilight set — were limited by the technology of early smartphones, but that was fine. Limitations create art. Cell phone novels read line-by-line, rarely in paragraphs, and use white space to lend their narratives poetic luster. Here’s an example from takatsu’s Move:

Like a lost soul I swim through insomniac night crowds and stumble into my tiny desolate apartment dropping my frozen suitcase

Narrative precedes concerns like rhyme and meter. If you’re familiar with prose poems, you can think of cell phone novels like poem prose, optimized for a mobile screen. Fans read cell phone novels how they were written, i.e. over long commutes.

They weren’t light reading, though. Stories were “dark, sensational, and sexual.” The first cell phone novel, Deep Love, follows a young woman, Ayu, who turns to sex work to save her dying boyfriend. She dies of HIV. Ayu conveys this all in confidence, so that the line blurs between character, hurriedly outlining her story, and author, pouring themselves into their phone with little filter. Authors describe a personal connection to the content of their narratives — the word we’d use now is “self-insert” — although Deep Love itself was written by a man in his thirties.

(By the way, I had a ton of trouble accessing the classic cell phone novels — Deep Love; I, Girlfriend — because the genre lived and died in Japanese. It originated in 2002, the year of “Hot in Herre” and Die Another Day. I read mostly excerpts from the second-wave Western cell phone novels of 2008, the year of ghost peppers, Bitcoin, Quantum of Solace. Maho iLand, the usual haunt for cell phone novels, remains active and free to read.)

As the cell phone novel climbed in reputation, three basic viewpoints emerged.

I sure do enjoy reading cell phone novels. (This was mostly the claim of young women, although by 2007 everyone from major publishers to literary critics had gotten a hand on the ball.)

Cell phone novels will destroy the author and the novel. They’re poisoning the minds of young people ew icky gross.

Aw, these are so precious. They’re almost like real literature!

The breezy style of cell phone novels, the sort of Notes app tone with no extensive editing, didn’t help their purchase with the literati. I see “substandard grammar.” I see “sudsy” and “cutesy.”

Even praises of the genre focused on its utility. Publishers reached out to cell phone novelists, offering them the chance to publish their work as a “proper book.” At least the girls are reading; maybe this whole cell phone fad will do some good; next they might read actual fiction.

It wasn’t all pretentious. National competitions recognized and uplifted talented young writers, outpourings of gratitude from fans flooded the often anonymous authors’ inboxes. And despite their grousing, traditional publishers did capitalize on popular cell phone novels, transmuting them into manga, anime, and “proper books.”

What’s continued to bother me about cell phone novels is this: Grown-ups and corporations insist on comparison. You know, when your nephew comes up to you talking about Fortnite and like, what do you have to compare it to? Kick the can? Hoop-and-stick? Minecraft?

The cell phone novel spawned from dizzyingly high cell phone use among Japanese teenagers, whose commutes could run an hour in both directions. Publishers, critics, journalists failed to understand the language and culture of SMS, so they oriented their beliefs around the 300-page paper-and-ink novel. You couldn’t just take it at face value.

Combine that with the culture-wide hatred of things that teenage girls enjoy (the Twilight thing again), and cell phone novels seem as doomed as their protagonists. Advocates and critics alike feared that the cell phone novel would blow up our relationship to literature, that as cell phones grew in ubiquity the written word would fall to the touchscreened abbreviation. But that’s not what happened. Instead they fell into obscurity. Why?

First off, cell phone novels are still being written. They just don’t make bestsellers lists.

More to the point: Traditional publishing could never trap the cell phone novel, because the cell phone novel existed as a counterpoint to it. Everybody had it backwards. They thought it was a new form of literature accessible to young people, when the whole point is that it was inaccessible to the elite.

Take the serialized format. When the modern novel began pouring out of Victorian England, they were expensive luxury items. Publishing houses ran full stories — including many that would become classics, including the works of Charles Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Alexander Dumas, and every Sherlock Holmes story — in weekly or monthly installments. It offset the cost, and the edge of your seat turned out to be the best seat in the house.

Paper and machines got cheaper. Soon you could spit out gazillions of novels, fill a bookstore, fill an Amazon window. You could publish it all in an eBook.

Serialized fiction comes with one distinct disadvantage, which is that it defers gratification. No launch parties. No release dates. No guarantee that anyone will still be thinking about you by the time your story wraps. Television proved that serialized formats can still work, but since the advent of streaming it’s a toss-up. Whether you drop a whole season or run week to week is a marketing choice (and a diminishing one).

Just a handful of genres survived deserialization. Comics have always been serialized, and I don’t know of any comic books popularly considered to be “proper” literature. (Visual storytelling remains rightly esteemed, but those are usually called graphic novels.)

Some writers serialize their fiction as an homage to earlier days. The Green Mile ran in six volumes. More recently, Salman Rushdie and Maragret Atwood have shown interest in serialized projects.

And finally, serialization dominates all areas of self-published webfiction. Fan fiction, Wattpad and Archive of Our Own, the webnovel and webcomic. Medium. The cell phone novel.

Traditional publishing flirts with serialization, but it thrives online for the same reason cell phone novels were written on trains and buses and while sitting around on holidays: these writers often lack the time and financial sufficiency to write and write and write. They pump out a chapter, then do the dishes or whatever.

Serialization diffused costs when publishing was very expensive. If you aren’t Random House, publishing is still very expensive.

Plus, serials lend themselves to collaboration. Victorian authors would often publish the first chapters of their novel without any idea how it would end. Ditto, cell phone novelists could put pen to paper and worry about the details later. Deep Love found its ending via fan mail, when a reader’s personal connection to sex work touched the author.

One more vestige of the cell phone novel is the tendency of authors to assume pseudonyms, rather than publishing under their own names. Cell phone novelists tended to guard their identities with extreme secrecy, however beloved their online presence became. Reasons varied. Some authors wanted to keep their writing hidden from family members, others wanted the work to stand on its own.

Few grasped at fame. Of the millions of cell phone novels on Maho iLand — and today, the hundreds of millions of stories on Wattpad — the handful of breakout stars represent a kind of survivorship bias. We know Koizora and The Kissing Booth because they got caught in public attention. Fifty Shades and The Love Hypothesis started as fanfiction, but as Jim Hines wrote, “All fiction is fanfiction. The only difference is one of degree.” Most writers never angle for acclaim.

They write because it feels like the thing to do.

One literary editor distinguished the cell phone novel from literature, saying, “One tells you what you already know.” What he should have said was, “One shows you yourself.”

Everyone approaches art hoping to be told something they already know. We approach textbooks to be told something we don’t know. Where no clear representation of self exists, somebody is bound to create one. That’s why it’s called “self-expression.”

What happened to the cell phone novel? It’s still there, hidden among billions of words of self-published webfiction, beside which the oeuvre of “real literature” is disappearingly thin. Whether or not they’ll put a dent in the universe doesn’t matter. Art serves the artist.

The cell phone novel was never a stable, well-defined object. You couldn’t hold it in your hand. In a culture of expensive tastes, art requires a budget, airplay, hype, skills, CGI. Few profit from this arrangement, and they guard it closely. Once, they tried to conquer the billions, too.

So publishing whammed its grave palm over the self-expression market, and came up with smoke. Poof.

Thank you for reading! I wanted to be super clear in my intentions with this post: Supernormal is about fun, and I hope it is fun. But talking about fun also means talking about power, identity, and real criticism.

If you can hang with that, then you can hang with Supernormal. Subscribe for more — it means the world.

DR