#5: Making the familiar strange

I needed to learn how to pick better road trip songs, so I turned to Russian formalism

You don’t want to go on a road trip with me. I get carsick easily, I have sciatica, we’ll need to stop like every hour. My taste in road trip music is no good at all.

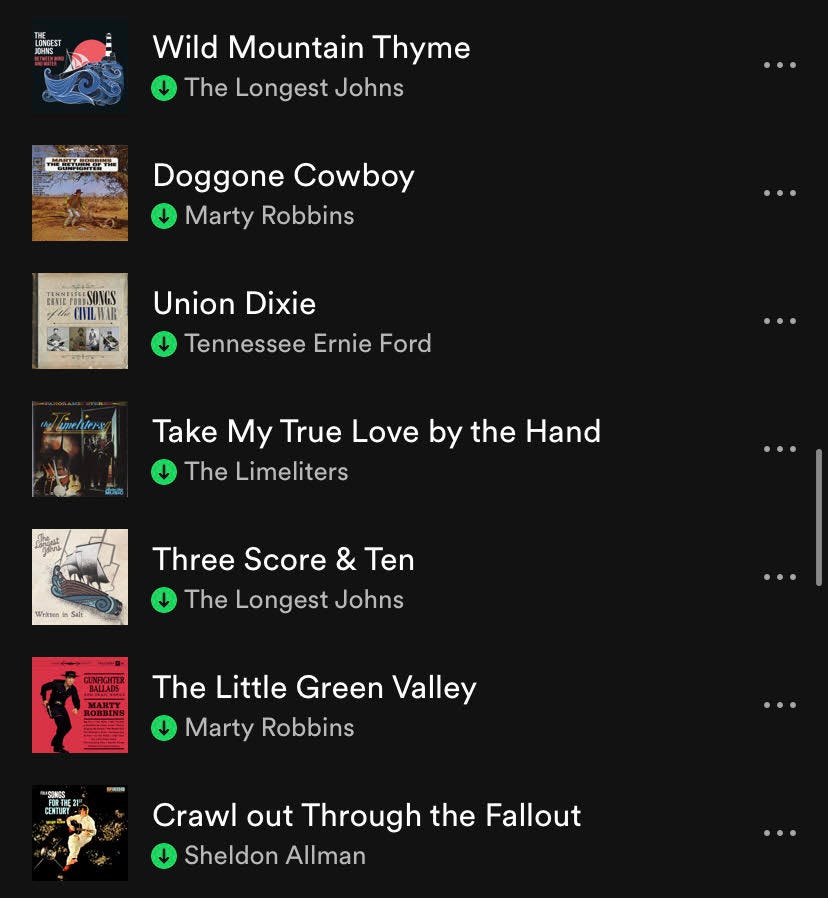

I mean, I like my music. It’s just, I always get embarrassed when it comes up on group playlists. Not like, “Lol, my taste in music is so bad. I’m really into Prokofiev right now and I just don’t think people will get it.” I mean nerd rock bad. I mean interstitial-numbers-in-musicals bad. After discovering that my Spotify Wrapped was a set containing all of both Assassin’s Creed IV sea shanty albums, I decided to stick with playlists my girlfriend made for me, which is the sonic equivalent of having someone else pick your outfits. Except, every item bore a Tennessee Ernie Ford-shaped stain that just wouldn’t come out.

I want to diagnose why my taste in music sucks on road trips. Spotify currently has no metadata to distinguish the cool from the corny — I think the platform’s base assumption is that everybody should just try to be cool — but in the deep lexicon of aesthetic philosophy there are terms that, when you learn to pronounce them, describe the ways we experience art. Qualities, techniques, emotions. As it turns out, a highly specific and sought-after emotion is the crux of a bad road trip song.

Now, full disclosure, I’m not a music theory guy. If you told me that every single song I love is in five-eight time, that would be news to me. I am a writer, though. You know, I get excited when the Jeopardy category is “19th century poets.” Song lyrics aren’t poems exactly, but they are poem-adjacent. One similarity, to quote an old professor, lies in function: all poems (and song lyrics) are either trying to make the unfamiliar familiar, or make the familiar strange.

There’s a third category, I guess, which is “start strange and stay strange the whole time.” Psychedelic music lives here. But whether a song wants you to understand it, or whether a song wants to confuse you — that covers just about all your bases. Thinking in terms of paintings, you can start to divvy artists like Hopper and Rembrandt from Picasso and Chagall. In literature, it’s Dickens versus Murakami. Both groups, ultimately, have something they want to say. Artists don’t generally aspire to enigma. The difference is that one does some of the work of understanding for you, while the other denies you the means to make sense of itself.

I think most popular songs fall under this first category of making the unfamiliar familiar. A song like Phoebe Bridgers’ “Kyoto” wants you to understand something about a complicated relationship. In the style of a diary entry or a cautionary tale, it explores the subject through its narrative. In “Here Comes the Sun,” George Harrison wants to communicate a feeling of relief following a long, dark period. He uses the metaphor of a sunrise.

Metaphor, narrative — these are teaching tools. They anchor something very abstract and indescribable to something concrete and describable. A metaphor’s “target” is never something you can hold in your hand. “Time is money” isn’t something we use to understand money. We compare the two because we think that the lessons we learn from our savings accounts, loans and impulse purchases will help us understand the march of hours.

Similarly, a good story will always anchor us to the main character. We can’t help ourselves. Personal narratives are among the greatest mechanisms for empathy we have.

These kinds of songs seem intuitively better for road trips: nothing in the song is working against you enjoying it. We ride the crests and troughs of the music together — verse, chorus, bridge — and end up with the same prize. We all ugly cry at the same lines.

So what about the opposite case? What if you were to take something familiar and use music to make it feel strange? You would have a very different kind of song.

For the sake of a running example, I’ll pick on They Might Be Giants. They’re my favorite band, and they’re by no means indie — they did the Malcolm in the Middle theme for crying out loud — but Gothamist did call fans of the band “grownup kids.” With hits like “Doctor Worm” and “Particle Man, Particle Man, doin’ the things a particle can,” we can’t really claim the optics of “cool people music.”

One of my favorite lyrics comes from “Can’t Keep Johnny Down,” which is a song about a paranoid asshole. The line I’m thinking of goes, “Some dude, hitting golf balls on the moon, bathroom in his pants, and he thinks he’s better than me.”

The line isn’t general or impressionist. It’s hyperspecific: they’re describing Alan Shepard, the first American in space and the fifth person to set foot on the moon. He literally drove two golf balls while on the moon’s surface. That kind of trivia is classic They Might Be Giants: a focus on minutiae at the expense of the bigger picture. Shepard did have a bathroom in his pants. He’s also, you know, an astronaut.

The band has been active for 40 years, and in that time they’ve developed a comprehensive library of techniques for making the familiar strange. Syntax, wordplay, personification — “Birdhouse in Your Soul” is sung from the perspective of a night light. At the last show I went to, they sang one of their songs fully backwards. This is not the behavior of a band that wants you to understand something better.

And yet, songs like these receive one of the highest distinctions in the philosophy of art. They’re so prestiged, a piece of jargon exists just to define the joy of experiencing such an artwork. From the desk of the Russian formalists, the word for a song about diaper-wearing astronauts and nightlights is ostranenie.

You can translate ostranenie as “making strange,” “pushing aside,” and most commonly, “defamiliarization.” It refers to an approach where the subject is construed so non-obviously, the audience is forced to consider it in a new way, probably for longer than they’ve ever considered it before. To take an example from pop art: one Campbell’s Soup can probably won’t come up on your mental radar. But see 32 Campbell’s Soup cans rendered in loving detail and hung up at the MoMA, and you’re bound to think of them in a new light.

The formalists were emphatically not talking about They Might Be Giants, or Neutral Milk Hotel, or Miracle Musical. They were talking about Tolstoy, Sterne, Wordsworth. They were talking about Real Art. In certain radical corners of formalism, ostranenie was considered the singular difference between “art” and “not art.”

At last, I have the answer I’m looking for. The reason my contributions to road trip playlists fall short is because, in fact, my music is a true and challenging aesthetic experience. It renews perception and forces the window-gazing masses to confront the facts of the world, in all their weltering complexities. I’m really into Prokofiev. They just wouldn’t get it.

Of course, I question this kind of checkbox approach to definitions of art. Somehow — and I’m sure this is just pure coincidence — they always end up separating an elite, intellectual class of connoisseurs from Cheeto-fingered plebeians. Terms you will find accompanying ostranenie include “estrangement,” “alienation” and “distance.”

Do you want to know another technique of ostranenie? Fourth wall breaks. When the characters in a story talk directly to you, they remind you that you are not a part of their world. It’s exactly the same as the 3D movie craze of the late aughts: billed as bringing you into the film by spilling it through the screen, the gimmick only ever served to make you feel like you were watching… a slightly worse quality movie. You remember that it’s “lights, camera,” not just “action.”

The trap these filmmakers fell into is similar to what Jeff Zacks, author of Flicker: Your Brain on Movies, calls the “willing construction of disbelief.” We assume disbelief is our natural state. After all, why would we believe in giant robots and parallel dimensions? But in reality, we show up ready to hear the story. Our brains evolved to trust, not to doubt. We come prepared to believe what we see, and our suspicions only compound in the face of many glaring inconsistencies.

When we listen to music, we don’t automatically bring a critical approach. Our senses need to be triggered by something in the artwork. Ostranenie is the deliberate triggering of those critical faculties. No trigger, no ostranenie. We’re free to ignore the boundary between ourselves and the art. We lose ourselves.

Neither type of song — defamiliarizing or familiarizing — is strictly greater than the other. I think whichever you tend to prefer is basically random. It may depend on your relationship to music. For me personally, I don’t go to music for strong emotional reactions (although, that’s not to say a song has never elicited such a reaction). But I cry frequently at TV shows. Video game narratives take a huge chunk out of me.

Songs about realization are great because they make you think about things. They can give you a really pleasant “aha” moment of realization. They suffer on road trips because everybody realizes at their own pace, and in their own way. And that’s usually not the vibe when you’re just trying to weather a long journey together. In that case, you want a song that disappears into the moment. You want a shared experience, not a car full of individual journeys.

The trouble with ostranenie is that, by definition, it can’t last forever. I’ve heard “Birdhouse in Your Soul” a million times — every They Might Be Giants fan has. It came out in 1990, and it has no new flashes of insight to give us. But every time I go to one of their concerts, I hope they perform “Birdhouse.” I know all the words, and so does everyone. The best song of the night is the one we all sing together.

What I’m having fun with lately

Diablo IV came out early this month. I’ve been interested in the series for a really long time. The first iteration of the hack-and-slash series came out in 1997, and it’s gone through all kinds of ups, downs, and changes since then.

chronicles the troubled release of Diablo III in his book Blood, Sweat, and Pixels, which is a great read if you’re interested in video games.Every once in a while I get super into Sudoku, and in my recent search for a good phone game I downloaded a couple Sudoku apps. One offers a clean, adless experience, but only lets me play once a day. One lets me play as much as I want, but it interrupts me every 15 minutes or so with a minute long ad. I really would’ve imagined we cracked this game by now, come on people.

I love good interviews. I think Hot Ones’ Sean Evans is maybe the greatest working interviewer, but I’ve been really enjoying Anthony Padilla’s “I spent a day with” interviews, too. The Vsauce one is my favorite so far.

Got super into game design the past week, at the expense of other things (including this very post!). It got me thinking back to some of my favorite dice pool systems. If you want a fun, very entry-level tabletop RPG, my friends and I had a blast with Magical Kitties Save the Day!, where you play as cats with superpowers.

Finally finished Kaguya-sama: Love is War - The First Kiss That Never Ends (yes it’s a mouthful, yes I’m pretty sure that’s the joke). The four-episode special wraps up season three of my all-time favorite show, and what I think is the best romantic comedy ever made if you can stomach anime. Worth a look if you like that sort of thing and have Hulu!

Thanks for reading! Since Supernormal is something like an apology for embarrassing art, I thought I should turn the spotlight on my own embarrassment — although admittedly, I feel like my taste in music has come a long way in the last couple years.

Anyhow, I wanted to experiment with getting a piece out in a week rather than a month. That failed obviously, so I won’t commit to a weekly post schedule just yet. But know that my hangup is time, not ideas. I’ve got plenty of stuff I can’t wait to tell y’all about. Stay tuned!

DR